It recently passed a year to the day since lockdown began in the UK.

As you probably already know, despite so much time spent at home neither our sleep quality, nor the quantity of hours have improved during this time.

Research has revealed the impact of sleeplessness has become especially prominent for healthcare workers, women and people of black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds (BAME).

Put simply, more of us are being affected by sleeplessness and insomnia – and the long-term effects on our mental health are starting to surface.

Below we share some tips on how to improve your quality of sleep and better support your team.

But first let’s look at the impact poor quality sleep can have on our lives.

Bad sleep is costing us

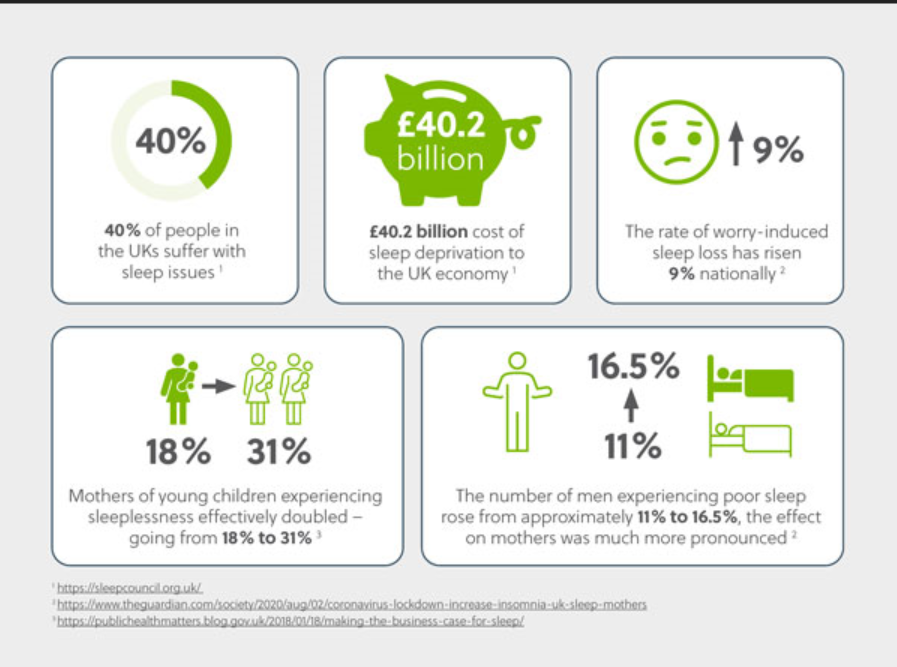

The Sleep Council UK has found 40% of people (in the UK) suffer with sleep issues. And the effects are costly.

Compounding this statistic is the £40.2 billion cost of sleep deprivation to the UK economy.

NHS inform defines insomnia as “difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep long enough to feel refreshed the next morning.”

People can experience insomnia in different ways, including short-term and chronic insomnia.

A few of the common causes include:

- Stress and anxiety

- Mental health conditions

- Lifestyle factors like caffeine and cigarettes

- Physical health conditions and medications

- Shift work

- Difficulty maintaining a regular sleep routine

With these in mind, it doesn’t come as a surprise that sleeplessness has become so widespread in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns.

We naturally sleep lighter when we are experiencing anxiety and over the last year, millions of people have experienced uncertainties relating to work, finances, health, changes to routine and significantly reduced social contact.

If our brains sense a threat to our survival, it can produce a heightened physical stress response – increasing our levels of adrenaline, cortisol and heart rate.

All of which don’t help our sleep and can affect our mental health.

Impact on healthcare workers

A global study conducted by the University of Ottawa found increased prevalence of psychological stress in populations affected by COVID-19.

Released in December 2020, it was found healthcare workers had reported significant increases in levels of insomnia and chronic mental health struggles.

Usually the impact of shift work can be enough to disturb a healthcare worker’s circadian rhythm, however compounding factors such as COVID-19, high levels of stress and high risk levels of exposure to the virus have contributed to these increases in sleeplessness.

These increases come as no surprise, given healthcare workers have worked longer and harder in high-risk conditions across the country, and the world.

The research found:

- A 15.97% increase in the prevalence of depression

- A 15.15% increase in the prevalence of anxiety

- A 23.87% increase in the prevalence of insomnia

- A 21.94% increase in the prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

The rates of these symptoms and disorders were three to five times higher than the rates reported by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

These findings – which will be used to develop better mental health programs – are early indicators of the severe/ongoing mental health problems healthcare workers may develop as the pandemic ends, or with the alleviation of lockdown restrictions.

Impact on women

While the rate of worry-induced sleep loss has risen 9% nationally (women and men), there have been dramatic spikes in some groups of people experiencing sleeplessness.

The University of Southampton discovered the number of men experiencing poor sleep rose from approximately 11% to 16.5%, the effect on mothers was much more pronounced.

Mothers of young children experiencing sleeplessness effectively doubled – going from 18% to 31%.

For women who had children aged 0-4, the rate rose dramatically from 19.5% to 40%. Similarly, the increase was 21.7% to 38% for those with children in the 5-18-year-old range.

Impact on the BAME community

Sleep issues also had a striking impact in vulnerable groups such as the black, Asian and minority ethnic community.

These communities experienced an 11.3% increase in sleep issues, going from 20.7% to 32%.

Vulnerable minority groups most likely experienced higher rates of anxiety from COVID-19 lockdowns due to higher rates of infection among those populations.

Also, minority and ethnic communities were more susceptible to economic difficulties like job loss, feelings of isolation and working to support multiple children or dependents.

Tips to improve your sleep and support your team

- Don’t email after the work day is over – Encourage your team, and yourself, to switch off as if you were leaving the workplace. They may check their emails anyway, but messages from their leader after hours will prevent them from winding down from the working day, regardless of when your request or task is due. Use scheduling tools so your message arrives the next morning instead.

- Don’t glorify sleeplessness or fatigue – Be disciplined in how and when you talk about working late or answering important calls after hours with your team.

- Be disciplined about the sleep choices you make – Know what time you need to go to bed to get your full 7.5 to 9 hours and write it into your planner, calendar or to-do list.

- Build a good ‘going to bed’ routine – Give yourself at least 30 minutes before your designated sleep time to calm your mind by avoiding your phone, tablet or computer screen.

- Good sleep is a group effort – Make sure your family understand why you are being so disciplined about going to bed, and how good sleep is beneficial to your daily performance.

- Eat well – Low G.I. foods will make sure you don’t wake before you should. This is especially important for shift workers. And of course avoid caffeine or alcohol to really get the better restful sleep.

- If you can, exercise regularly – Not always easy in lockdown, but getting outside for a walk in the daylight in the morning triggers your brain into action for the day, and helps your body get the most out of your sleep when it gets dark. Regular scheduled physical activity also helps let your body know when it’s time to rest.

- Support your team to take rest and recovery breaks – It’s easy to stay glued to our screens all day, so communicate with your team and encourage breaks. This is especially important for those who are working through injury, illness or personal challenges. They will recover faster with good quality rest, resulting in more sustainable performance outcomes.

Further information

- Tips to improve your sleep – Mind.org.uk

- Adults: advice and information – The Sleep Charity

- The impact of sleep on health and wellbeing – CiC blog

Sources

- Healthcare workers have increased insomnia, risk of severe mental health problems: COVID-19 study – EurekAlert

- The ‘coronasomnia’ phenomenon keeping you from getting sleep – BBC

- Coronavirus lockdown caused sharp increase of insomnia in UK – The Guardian

- Napping – Sleep Health foundation